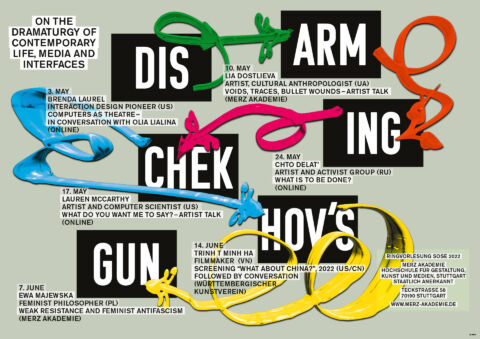

A manifesto for a series of lectures and conversations at Merz Akademie in summer semester, 2022

The mantra passed down from generation to generation “you can’t put a loaded gun on stage if no one means to fire it” first appeared in a letter Chekhov wrote to a young writer, criticizing the way his vaudeville was structured:

Dear Alexander Semyonovich!

I received your vaudeville and immediately read it. It’s beautifully written, but its architecture is obnoxious. It’s not scenic at all. Think about it. Dasha’s first monologue is completely unnecessary. It stands out like a sore thumb. It would have fit if you wanted to make Dasha more than just a supporting role, and if this monolog – that promises a lot to the audience – had anything to do with the content or the effects of the play. You can’t put a loaded gun on stage if no one means to fire it. You can’t make promises. Let Dasha be silent altogether – that’s better.[1]

Dasha, her first monologue and its unkept promise did not go down in history, but the analogy of the loaded gun left on stage unfired did: Chekhov’s Gun – the dramaturgic principle that advises authors to remove irrelevant elements from their stories, be it in novels, theatre plays, or later in films and television scripts. Closer to the end of the 20th century, the concept also entered the digital realm, from interactive fiction to Extended Reality.

But it is not only in literature and entertainment of all genres and media where playwrights’ rules are applied. Dramaturgic principles have long taken over the socio-political spheres of our lives that are computer mediated since digital environments like Aristotelian drama happened to be an “imitation of an action with a beginning, middle and end, which is meant to be enacted in real time”, as Brenda Laurel pointed out in Computers as Theatre, 1991.

A century after Chekhov warned against leaving unfired guns on stage, Laurel recognized the same pattern – “gratuitous incidents”[2] and the unwanted effect it can have in the design of software, when on staging an interactor’s experience. To properly script user’s expectations and actions no minor detail standing in the way of “constraining what is probable”[3].

30 years later software got more sophisticated, complex, and literally invisible. It means that today these constraints need to be tighter than ever before. Designers of chatbots, robots, and immersive environments take care that guns are fired or nonexistent. To succeed in fully automated environments, CGR – Chekhov’s Gun Recognition[4] algorithm, was suggested recently…and then there is the concept of Schrödinger’s Gun[5], a combination of Schrödinger’s Cat and Chekhov’s Gun, an algorithm that can render any numerically represented element from gratuitous to necessary. Everything can be turned into a loaded gun in computer generated environments.

Outside of tropes and virtual worlds, the playwright’s principle has become a curse. There is Alec Baldwin’s Gun that was supposedly just a prop, and currently, there are Putin’s guns that we so much wanted to believe were just for show, not loaded at all, or at least would not fire.

What if Chekhov’s letter was never written, got lost or was simply ignored? What if the unimportant Dasha had a chance to recite her unnecessary monologue?

Imagine a world where our lives weren’t shaped by the predictable laws of drama and we were not a part of Aristotle’s tragic progression.

Leave the guns unfired and give the stage to Dasha!

[1] Т. 3. Письма, Октябрь 1888 — декабрь 1889. — М.: Наука, 1976. — С. 273—275. [my translation] Source http://chehov-lit.ru/chehov/letters/1888-1889/letter-707.htm

[2] Laurel B, Computers as Theatre, 1993 p.74

[3] Ibid., p.76

[4] Tikhonov A., Yamshchikov I. Chekhov’s Gun Recognition, 2021 https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.13855v1

[5] Robertson J., YoungR.M., Finding Schrödinger’s Gun, AIDE, October 2014